The examples enumerated above concern the law of nations, or the relations between sovereign entities (or 'polities', with the expression used American legal historian Lauren Benton in a recent stimulating article on international legal method). Yet, we cannot assume that the law of nations corresponds to a well-defined separate legal order in this period. We should rather frame it as a discourse serving to explain power relations between sovereigns. The frequent use of feudal law as 'vernacular' legal language creates interpretative problems as soon as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation surfaces. This construction, 'monstro simile', according to Samuel Pufendorf (under his pseudonym Severinus de Mozambano, as displayed on page 400 of De Statu Imperii Germanici below), was constantly caught between the recognition of the Empire's members' real domestic power (ius territoriale), their ability to conclude treaties with outside players (ius foederis), on one hand, and, on the other, their feudal oath of loyalty (auxilium, consilium) to the Emperor and Empire as caput imperii.

The focus of this modest blog post concerns the most polemical internal German question of the war. Within the Holy Roman Empire, the Habsburg dynasty had managed to have its members chosen by a majority of Electors as either Emperor or King of the Romans. The house of Wittelsbach constituted a potential rival. Its members held the hereditary electorates of the Palatinate (Heidelberg, Mannheim, equally connected to the duchies of Berg (Düsseldorf) and Jülich) and Bavaria. Since the Nine Years' War (1688-1697), duke Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria ( had been appointed as governor-general in the Spanish Netherlands, a composite geopolitical entity with as its core the Duchy of Brabant and the County of Flanders. His brother, Joseph Clement, had been elected Archbishop of Cologne and Bishop of Liège.

The Wittelsbach princes split at the beginning of the War of the Spanish Succession. Max Emanuel (1679-1726) and Joseph Clement (1671-1723) opted for an alliance with France. John William (Johan Wellem), Elector of the Palatinate and Duke of Berg and Jülich (1658-1716), chose the Habsburg side. Max Emanuel's choice was of major strategic importance. The conflict over the succession of Charles II of Spain (1661-1700) would involve war on all French borders. Thanks to the appointment in Charles II's will of Philip of Anjou (1683-1746), Louis XIV's second grandson, as King of Spain, the Pyrenees were not to be feared. Yet, the Italian and Flemish fronts, where French troops had time and again fought against Dutch, Spanish or Austrian forces, were major points of concern.

(Joseph Clement of Bavaria, painted by Hyacinthe Rigaud; Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Louis XIV arranged things as to have his grandson delegate the administration of the Spanish Netherlands to France. The troops which had been quartered in fortifications by the Dutch after the Peace of Rijswijk (1697) had to leave early in 1701 (1). Marshal Boufflers (1644-1711) and Max Emmanuel could thereby simply occupy the gateway to Paris against the allied army. Likewise, the possessions of Joseph Clement along the Rhine in the electorate of Cologne, or along the Meuse in the prince-bishopric of Liège, pushed the front even further away from the French border (2). Finally, the duchy-electorate of Bavaria constituted an advance zone of attack to threaten Austria itself (3).

(Max II Emanuel painted by Vivien during the War of the Spanish Succession; Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Although the 'Bavarian' allies could not contribute much to the French military effort, these geopolitical advantages were considerable. France had had to fight barely without allies against the whole of Europe (including Habsburg Spain and Bavaria) during the Nine Years' War.

2.

This favourable starting position, however, did not last very long. The Duke of Marlborough (1650-1722) managed to gain control of Cologne and Liège (1702-1703) and then united in 1704 with Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736), to crush the army of Max Emanuel and Tallard (1652-1728) at the battle of 'Blindheim' (Blenheim). The French commander was taken prisoner, and Max Emanuel saw his Electorate occupied by Austrian forces.

The ius foederis recognised to the members of the Empire in the Peace of Osnabrück (Instrumentum Pacis Osnabrugensis) allowed them to contract alliances with third parties inside and outside the Empire. Yet, this could not violate the Reichsfrieden (peace of the Empire). Any treaty threatening the internal stability was forbidden, since it would violate the feudal bond of loyalty. Consequently, Emperor Joseph I (1678-1711), who succeeded his father Leopold (1640-1705), saw an excellent opportunity to deal a crushing blow to the House of Habsburg's competitors.

On 29 April 1706, the Emperor issued two letters patent condemning the attitude of the Wittelsbach electors. The first document can be found on page 191 of volume VIII/1 of the Corps universel diplomatique du droit des gens, the seminal treaty collection edited by Hugenot 'newsagent' Jean Du Mont in the Hague.

The Emperor targets the 'pernicieux desseins & mauvaises resolutions [sic]' undertaken by Joseph-Clement and his elder brother against the late Emperor Leopold, as well as the 'Alliances défenduës [sic]' concluded with France, in order to execute their pernicious plan. As evidence, Joseph I cites their 'propres Ecrits', but also the 'crimes de dangereuse consequence qu'ils ont commis aux yeux de tout le Monde'. Joseph Clement had been collecting troops with French money to fight in the electorate of Cologne (territory of the Empire), without the consent of the Chapter of the Cathedral, against the exhortations of the Chapter to pay respect to the Empire and Emperor, conformably to the feudal 'foi et hommage' Joseph Clement owed them.

In spite of numerous efforts to convince the Archbishop by 'voies douces', the Emperor and the Empire could only try his case, proclaiming by 'Sentence judicielle' his dereliction of duty, and confiding the latter's execution to the princes and circles of Westphalia, the Lower Rhine and the Electors. Joseph Clement was hoped to return to 'himself', recognising his obligations towards 'God, the Emperor, the Empire, the Chapter and the Estates of the Empire of whom he depended'.

Yet, Louis XIV and Max Emanuel kept Joseph Clement in their conspiracy. The Archbishop gave permission to bring troops from the Southern Netherlands into Cologne and Liège, occupying their fortifications. Joseph Clement, according to Joseph I, did not have the necessary legal authority to allow for the intrusion of foreign troups. '[il] ne les possedoit [sic] que comme Gouverneur, avec certaines restrictions, en vertu de l'Union des Païs hereditaires [sic] & autres Droits'.

Joseph Clement's stubbornness ('opiniâtreté') left no other option than to deprive him of this competence to administer, but also to declare his destitution according to the Constitutions of the Imperial Chamber (Reichskammergericht) and the resolutions of the Imperial Diet (Reichstag). His effective resistance and opposition against the judicial sentence (jugement judiciel) has caused him the loss of all Prerogative (as a man of the church), and all beneficia enjoyed from the Emperor and the Empire. The Emperor refers, for the basis of the sentence, to the Ban Impérial & de l'Empire contre les Séculiers, applied by analogy to the Archbishop.

Joseph Clement did not stop here, but decided to persecute the members of the Cologne chapter, extraditing some of them to the French, which have had them imprisoned and have exerted revenge 'd'autres voies', after disseminating 'toutes sortes de Pasquils & de Libelles diffamatoires' against the Emperor and the main members of the Empire, having taken the title of 'Arch-Chancelor' in Italy the defense of the rebel and 'felon', the Duke of Mantua, bringing the latter to 'disobey' the Emperor.

In the next passage, Joseph I tries to legitimate the use of force against the forces of Cologne in the campaign of 1702. This first year of genuine campaigning brought a confrontation between the Duchy of Berg (allied to the Emperor through Elector Jan Wellem of the Palatinate-Neuburg) and the Elector of Cologne (allied to France). French forces occupied the old imperial castle of Kaiserswerth. The ensuing siege destroyed the castle to the state it currently remains in.

(the ruins of Kaiserswerth near Düsseldorf; image source: Wikimedia Commons)

(the siege of Kaiserswerth; image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Joseph Clement, according to the Imperial letters patent, had been preparing for war in his territories, 's'étant chargé avec plaisir de tous ses propres crimes & de ceux des autres'. Leopold I could not have done otherwise than to take arms against the French and 'sa Faction'. Alas, a lot of blood has had to be spent. The Emperor discovered 'quantité de piéces [sic] et autres choses frivoles, remplies de stile François' (see for example here) which declared 'rondement' that no offer whatsoever, even made to his advantage, would be enough to convince Joseph Clement to return to the strict observance of his duties as a Prince of the Empire. The so-called 'Burgundian troops', raised by Max Emanuel in the Southern Netherlands, would be kept in Cologne.

Joseph Clement is accused of having tried to bring the city of Cologne to neutrality by force, of organising pillages in the neighbouring duchies of Berg and Jülich, and by the 'mauvais traitement qu'il a fait aux Habitans de l'un & de l'autre Sexe', by using a great number of French soldiers. Joseph Clement would have prided himself on these 'choses dignes d'admiration & glorieuses'. After the military defeat against the allies, the Elector would have opted to 'abandon' his Electorate and the Principality of Liège, leaving to the French the city of Bonn, his 'Residenz', and following with his 'Suite' a French escort, passing physically over to the 'Enemies of the Empire'.

As a consequence of the judgment pronounced against him, the Emperor has no other option but to exclude Joseph Clement of the Dignity and the Enjoyment of any rights of the Members of the Empire. His crimes of Laesio Majestatis, his 'désobéïssance [sic] opiniâtrée' and other 'gross errors' cannot give rise to a different conclusion. The Golden Bull of 1356, the Constitutions of Emperor and Empire the 'peace of the land', the most recent Statutes of the Empire, and the most recent decisions of the Emperor and The Empire, urge to pronounce a penalty.

No vassal of the Empire, of whatever status or condition, can have any communication with Joseph-Clement, can house him or 'donner le Couvert', give him anything to eat or drink, furnish whatever things possible, any help or assistance, or bequeath him with a legal title, nor receive in their 'guard and protection'. Those who have been his vassals, subjects, officers, inhabitants or 'dependents', ecclesiastical and secular, cannot have any kind of 'égards' for Joseph Clement, nor receive from him or his entourage, any kind of orders. The only possible loyalty is that to the Emperor and those appointed by him to take over from Joseph Clement. Any soldiers still in Joseph Clement's service have the obligation to switch sides, and to oppose their former master's plans, to 'do him all possible wrongs and damaged', in order to regain imperial grace and generosity.

All those previously engaged or obliged towards Joseph Clement, or those who think they are, become absolved of their oath of loyalty, duty, observance, intelligence and alliance, of an kind. Even more, since Joseph Clement's betrayal dates back to his alliance with France, there oaths do dissappear retroactively, 'étant nulles & sans force depuis sa felonie [sic], & Crime de Leze-Majesté'.

Finally, all contrary Imperial 'Graces, Privileges, Franchises, Customs & Usages' are deemed void and revoked. Joseph reaffirms at the end that the legitimacy to take such an order derives from his 'Imperial Roman authority'. It is no surprise that the name of Friedrich Karl von Schönborn, Head of the Imperial Chancery (Reichskanzlei) appears next to that of the Emperor. Friedrich Karel is the nephew of Lothar Franz von Schönborn, Archbishop-Elector of Mainz and Vice-Chancellor of the Empire.

(image: Lothar Franz von Schönborn; Source: Wikimedia Commons)

3.

Max Emanuel's case differs on material grounds, but also in legal qualification. His betrayal is clearly worse than that of his younger brother. He is accused directly from harbouring an 'esprit d'ambition démesurée', animated in part by 'une haine secrete [sic], inveterée [sic], & illegitime [sic], against the Emperor, his Lord and Cousin. This mention proceeds from the first marriage of Max Emmanuel with Maria Antonia of Austria, daughter from Emperor Leopold I's first marriage to the Spanish infanta Margaretha Theresia. Joseph I was a child of Leopold's third marriage to Eleonora Magdalena of the Palatinate-Neuburg (sister of Elector Jan Wellem of the Palatinate, Duke of Jülich and Berg, or the other branch of the Wittelsbach family).

(Image: Maria Antonia of Austria, daughter of Emperor Leopold I and Margareta Teresa of Spain, half-sister of Emperor Joseph I; wife of Elector Max Emanuel II of Bavaria; source: Wikimedia Commons)

Max Emanuel is reproached to have dumped all 'love, duty, honour and loyalty' due to the 'archducal House' and the late Emperor and Roman Empire. Certainly, Max Emanuel had conspired with Louis XIV in order to lower the Empire. Yet, foremost (sur-tout), he had been set on ruining the late Emperor and the archducal House. To this end, Max Emanuel delivered the Spanish Netherlands, whose guard and government had been bestowed on him, to France 'par un Esprit de revolte [sic] & de felonie [sic]'. His representative to the Regensburg Diet (Reichstag) had to act on behalf of Philip of Anjou and the 'Circle of Burgundy', in order to oppose Leopold I. Joseph Clement would have been maliciously seduced to conclude a forbidden alliance, and allow French troops -'derisory' called Burgundian troops- into the Electorate of Cologne and the Diocese of Liège.

(image: plan of the city of Liège and its fortifications, 1702; Source: Europeana/Rijksmuseum)

Evil genius Max Emanuel is said to have incited the 'Louables Cercles de Franconie & de Suabe' to join him against Leopold. He astutely delayed proceedings in the Reichstag against France and his allies. As a tyrant, Max Emanuel would have threatened all those unwilling to assist in the execution of his cause. Subtly, he seized the Imperial city of Ulm, on Our Lady's Day. He alone has had the temerity to ignore the determinate plans of all the Estates of the Empire, their declaration of War against France, the Duke of Anjou and accomplices.

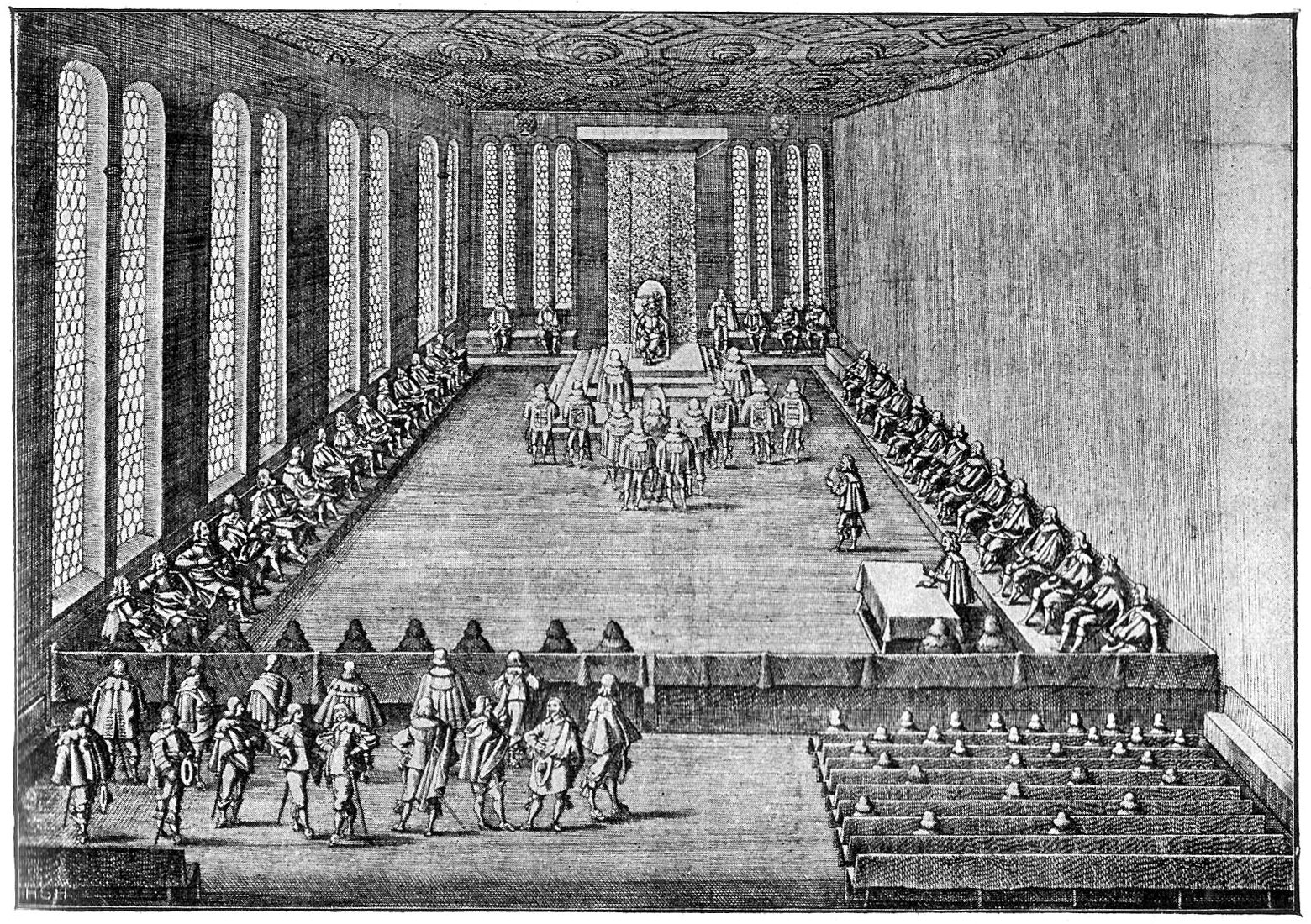

(Image: Imperial Diet in Regensburg, 1640; source: Wikimedia Commons)

Max Emanuel has annexed parts of the Emperor's lands, or those of other princes, to become ordinary provinces of Bavaria, using enemy troops. He exacted contributions, pillaged, murdered and burnt, sparing nor churches or other sacred places. On Easter, he has laid siege to Regensburg, the imperial town which housed the Perpetual Diet of the Empire. When the Imperial Free City fell to his troops, Max Emanuel pretended to annex it to his proper domains. Proof does not need to be found in the perpetually ongoing negotiations, but solely in the rivers of Christian blood spilled, the abundantly flowing tears from an 'infinite number of persons', moaning for a very long time, and still imploring divine and human vengeance. Max Emanuel and his 'Suppôts' have even tried to get the 'constante Porte Ottomane' on their side, even if this had been to no avail, since the Sultan 'sçait bien mieux qu'eux tenir sa parole'.

(image: Francis Rakoczy, Hungarian rebel leader; source: Wikimedia Commons)

Max Emanuel had incited the 'sujets Rebelles de Hongrie' to persevere in their revolt. Indeed, in 1704, Austria's case was thought to be precarious. While Tallard and Max Emanuel could threaten Vienna from the West, the revolt of Francis Rakoczy posed considerable problems in the East, outside of the Empire. The Emperor argues that Max Emanuel had offered himself as leader to the Hungarian rebels, inciting them to refuse any kind of mediation or compromise with Vienna.

(image: Bavaria ad Obsequium Rediens, or Bavaria reduced to submission by the Emperor; Source: Museum Rotterdam/Europeana)

Max Emanuel, conversely, would have rejected all 'generous' offers from Leopold I or Joseph I. Even enlargement of his territories in Schwaben were insufficient to satisfy his 'desirs [sic] immoderez'. Max Emanuel persevered in his pernicious and 'impious' plans. The crushing defeat of Blenheim had not brought him to abandon 'the Enemies of the Empire'. Max Emanuel had remained among his outrageous company, 'sans le moindre repentir', nor any sign of conversion.

(image: Battle of Blenheim - tapestry by Judocus de Vos in Blenheim Palace, erected by the Duke of Marlborough with a gratification received from Queen Anne to thank for the victory; source: Wikimedia Commons)

Therefore, the only possible conclusion is to declare that the 'former Elector and Duke of Bavaria, Count Palatinate of the Rhine, Landgrave of Leuchtenberg' has been put under the 'Ban & Arriere[sic]-Ban' of Emperor and Empire. De facto, he has fallen under all 'punitions & peines' normally derived from this kind of declarations, 'selon le Droit & les Coûtumes'. He is deposed and should be considered as such with regards to all 'Graces, Freedoms, Rights, Regalia, Honours, Charges, Titles, Fiefs, Properties, Patronage, Lands, Goods, Men and Subjects', in verbatim the same terms as his brother Joseph Clement.

(image: Emperor Joseph I; Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Likewise, all who joined Max Emanuel, or chose his party, suffer the same fate. The Elector has been put outside the 'Peace & Protection' of the Emperor, as well as that of the Empire. He is thus in 'our disgrace and incertitude', for having put himself in that situation. The following orders are similar to those pronounced against Joseph Clement:

(1) all privileges, graces and beneficia are cancelled, counting from the beginning of the felony

(2) subjects and vassals (especially soldiers) can disregard their oath of loyalty and are encouraged to oppose all possible obstacles to Max Emanuel

(3) all contrary Imperial declarations or measures are void

4.

The Emperor was not free to act as he pleased. The Peace of Westphalia had installed constitutional limits on the powers of the Pro-dominus (literally 'over-lord') of the Holy Roman Empire. He was tied to the approval of the Reichstag (Imperial Diet), since the collective corpus of the Members of the Empire was said to be jointly sovereign. Consequently, Joseph I's harsh words, although they almost read as classical medieval discourse, had to receive approval.

On 10 May 1706, 11 days after the two letters patent had been issued in Vienna, the Imperial Diet received an 'Imperial Commission Decree' requesting to accept the measures decided against Max Emanuel and Joseph Clemens. The Bavarian princes had behaved 'grossierement [sic] and intolerablement [sic]', having drifted far away from their duties, having undertaken 'quantité d'Intrigues seditieuses [sic], pernicieuses & violentes malversations', by their breach of the Imperial Peace ('infraction à la Paix', in German Reichsfriedensbruch), against the 'Grandeur' of the Emperor, against the Freedom of the Empire and against its Constitutions. They persisted in 'desobéïssance [sic]', revolt and 'damnables desseins', ignoring not only the fatherly 'Weisungen' of the Emperor, but also proposals of mediation and accommodation emerging from 'les fideles [sic] Princes et Etats, & par la Diete [sic] même, qui leur étoit bien intentionnée'. The Wittelsbach princes have thrown themselves into the arms of 'des Ennemis jurez & déclarez de l'Empire'.

Since the representatives in Regensburg had 'contributed in part to imagine and counsel generously, which was good and necessary', it seemed almost superfluous to recall what was prescribed by the Golden Bull, the Constitutions of the Empire and Emperor, the 'Peace of the Land', the Imperial Capitulation sworn at the Election of Joseph I in 1705 as well as the Imperial decisions taken in the course of the war. Joseph I could not have done anything else but 'le devoir de la Charge d'Empereur', punishing 'selon leurs demerites [sic]' both brothers: 'infracteurs de la Paix, Parjures, Felons, Contempteurs de la Liberté & des Loix d'Allemagne [...] pour servir d'exemple aux autres'.

The document is communicated to the Diet 'pour lui servir d'avertissement & satisfaire à la Coûtume'. The latter formulation indicates that the Emperor considers referring the affair to the Diet as a mere declaratory procedure. The legal basis in 'Custom' highlights the feudal origins of Imperial power: the declaration is meant for the Members of the Empire, 'pour servir d'avertissement'.

The brief eschatocol of the document states that the 'High & eminent Princes, Electors and Estates, the excellent Counselors of the Empire, the Ambassadors and Envoys did not want to obstruct the Will and Order of his Imperial Majesty'. Quite the contrary: they 'conformed themselves to it and persevered in that attitude'.

5.

An analysis of this text cannot -of course- be complete without the necessary secundary historical and legal-historical literature. In the first place, Reginald De Schryver's monography on Max Emanuel of Bavaria and the European ambitions of the House of Wittelsbach (published in the series of the IEG in Mainz), the older works of Legrelle (1888-1892), Klopp (1885) and von Noorden (1870-1882). Next, the concise and informative thesis of Rüdiger Freiherr von Schönberg (Das Recht der Reichslehen im 18. Jahrhundert, CF. Müller, 1977), but also the recent work by Wolfgang Burfdorf on Protokonstitutionalismus. Reichsverfassung in den Wahlkapitulationen der römisch-deutschen Könige und Kaiser 1519-1792 (published in the series of the Bavarian Academy of Science in 2015) can help to identify the exact nature of Joseph I's positioning. The Battle of Blenheim and its aftermath allowed the Emperor to reclaim a certain superiority.

As Guido Braun's elaborate study (2010, Pariser Historische Studien) on the knowledge of German Public Law in French 17th-18th century diplomacy (open access) illustrates, the house of Habsburg had at first been confronted with anti-imperial sympathy for France. Yet, the Turkish War of 1683 and Louis XIV's hegemonic temper during the Dutch War (1672-1679) had reversed the situation. Military success from 1704 allowed for remarkable acts of audacity, such as the punishment inflicted on Max Emanuel and Joseph Clement, or the confiscation of the Duchy of Mantua. In the latter case, it could be argued that the Imperial Diet's competence and the application of the Peace of Westphalia were irrelevant, since Italy fell outside the scope of this arrangement.

(image: Palazzo Ducale, Mantua; Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Yet, the situation can also be approached from the other end of the war. Article XV of the Treaty of Rastatt, which ended the bilateral conflict between Louis XIV and Charles VI, Joseph I's younger brother and successor in 1711, imposed the reintegration of the Wittelsbach princes. The Treaty of Rastatt was transformed into a general Peace Treaty between the Empire, Charles VI and Louis XIV at the conference of Baden (in present-day Switzerland, Aargau) (see here for a German translation of the Latin original).

Rastatt and Baden were painful moments for Charles VI, in the sense that this monarch had to recognize the factual impossibility of a total Habsburg triumph in the War of the Spanish Succession. The French candidate, Philip of Anjou, would rule on the Iberian peninsula and in the colonies. Charles would only conclude a bilateral peace treaty with Spain in 1725 (see my paper published on the subject in the Yearbook of Young Legal History 2010, as well as chapter 3 of Balance of Power and Norm Hierarchy, 2015). Charles VI could have signed for peace at the Conference of Utrecht (1712-1713), but withdrew his delegation. Since Britain, the Dutch Republic and Prussia had withdrawn their troops, the Emperor's army under Eugene of Savoy had to stand alone against that of Marshal Villars. Unsurprisingly, after an unfortunate campaign on the Franco-German border, peace was brokered between two military men.

(image: allegory on the Peace of Rastatt, 1714; source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Treaty of Rastatt that the Emperor and Empire would consent in the 'rétablissement général [...] et entier' of Max Emanuel and Joseph Clement, in all of their 'Estates, Ranks, Prerogatives, Regalia, Goods, Electoral Dignities and Rights, just as they have enjoyed them, our could have enjoyed them, previous to the start of the present War, belonging either to the Archbishopric of Cologne & other Churches [...], or to the House of Bavaria, mediately or immediately'. What could be the motive for such a sudden turn in Imperial positioning ? The answer was not to find in a reassessment of internal legality (i.e. within the Imperial legal order), but with 'les motifs de la tranquilité publique'.

(image: Charles VI as emperor by Meyttens; source: Wikimedia Commons)

I argued elsewhere, in a quite comprehensive fashion, that the stabilization of Europe after the War of the Spanish Succession was based on a logic of norm hierarchy: political compromises enshrined in treaties had to receive priority over constitutional law. French and British diplomats consistently applied this reasoning from 1716 to 1725, with at least a rhetorical continuity until well in the 1730s. For the case of France, this was hotly debated and contested by domestic lawyers like d'Aguesseau (I refer to my contribution in the 2016 volume Penser l'ordre juridique médiéval et moderne, ed. X. Prévost & N. Laurent-Bonne or to my CORE Working Paper on the same subject). Yet, diplomatic practice witnessed the consistent application of a reasoning of priority, leading to the analogous application of treaty precedence to the arrangement of Italy in the light of the prospective extinction of the Medici and Farnese dynasties in Parma, Piacenza and Tuscany (see chapter 2 of Balance of Power and Norm Hierarchy, or my contribution to the edited volume Thémis en Diplomatie, ed. N. Drocourt & E. Schnakenbourg).

(image: siege of Huy by the allies in 1703; Source: Europeana/Rijksmuseum)

In January 2017, at the occasion of the conference 'The Art of Law' in Bruges, I had the opportunity to discuss the iconography of the Almanach Royal for 1715. The engraving for this publication depicted Louis XIV and Emperor Charles VI amidst other European sovereigns, crowned by the virtues of peace. I interpreted the depiction of the horizontal agreement between Louis XIV and his 'Fellow Monarchs' (to use Ragnhild Hatton's expression) as a different strategy to seek legitimacy in representation, compared to earlier depictions of international relations and diplomacy, when Louis XIV was portrayed as unilaterally imposing order on Europe (mainly from 1668 to 1684).

(image: Almanach Royal 1714, représentant l'Union des Princes, par la Paix Générale; source: Europeana/Gallica)

(image: the failed siege of Brussels; Source: Europeana/Rijksmuseum)

Likewise, Charles VI had to accept the reintegration of the Bavarian princes, depicted in the Almanach. This could be seen as a small triumph for French diplomacy, especially since Joseph Clement had lost Cologne and Liège in 1703, Max Emanuel lost Bavaria in 1704, and the major part of the Spanish Netherlands in 1706 (Brabant and the main cities of Flanders) and 1709 (Hainault). The Bavarian allies had turned into a nuisance. Max Emanuel's credibility had fallen very low. He appeared before the gates of Brussels in November 1708, hoping the capital of Brabant would open its gates to its former governor-general, but these hopes were quickly dashed. Max Emanuel was bequeathed with the sovereignty over the remaining French-controlled parts of the Spanish Netherlands, mainly the County of Namur and the Duchy of Luxemburg by Philip V of Spain on 2 January 1712 (CUD VIII/1, nr. CXXIV, 288), on the basis of 'ce que le Roi Très-Chrétien nôtre Ayeul a negocié [sic] & conclu le 7. Novembre 1702, en nôtre Nom, & de nôtre Consentement'.

Article XV of the Treaty of Rastatt states that Max Emanuel and Joseph Clement would have the right to send out plenipotentiaries to the general congress of peace in Baden, that all furniture, stones, gems and other personal belongings taken from them will be returned 'de bonne foy' [...] since the occupation of Bavaria, of their palaces, castles, towns, fortresses and any kind of places which belonged to them or would still come to belong to them. The restitution of rights stopped all claims against both sovereigns. Nevertheless, pending disputes could be initiated again according to the competent tribunals and established procedures ('voies de justice établies') of the Empire. Older ecclesiastical privileges and rights (to the benefit of the Chapter and Estates of the Archbishopric of Cologne) would of course remain in force.

(Image: map of the long and irregular Electorate of Cologne by Sanson (1674); source: Europeana/Gallica)

In return for their reinstatement, 'lesdits deux Seigneurs de la Maison de Baviére' renounced all possible 'pretensions, satisfactions or compensation for damages' against Empire, Emperor or the House of Austria stemming from the War of the Spanish Succession. Claims originating before the outbreak of the War, however, were considered to be still valid, if pursued through the ordinary ways of justice within the Empire.

Once reinstated, Joseph Clemens and Max Emanuel were obliged to obey and remain loyal to Charles VI, just as other Electors and Princes ought to, implying the duty to ask and accept as it should (deüement [sic]) the renewal of the Imperial investiture for their 'Electorates, Principalities, Fiefs, Titles and Rights, in the manner and terms prescribed by the Laws of the Empire'. In exchange, 'all that happened from either side, in the duration of the war', would be 'mis à perpétuité dans un entier oubli'. So far for all the alleged 'murder, pillage and burning', or the 'bad treatment' inflicted by French troops to 'inhabitants of either sex'... alleged in 1706 by the Empire and Imperial Diet !

Article XVI foresaw a 'general amnesty' for all 'Ministers, Officers, as well ecclesiastical as military, political and civil' on either side. All would be reinstated in the 'possession of all goods, charges, honour and dignities, just as before the war', enjoying a 'general amnesty for all preceding events', on the condition of reciprocity concerning 'subjects, vassals, ministers or domestics' having served the Emperor and Empire for the duration of the war. Any molestation would lead to the suspension of the treatment enjoyed by their Bavarian counterparts.

_-_Portr%C3%A4t_Kaiser_Karl_VI.jpg)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten