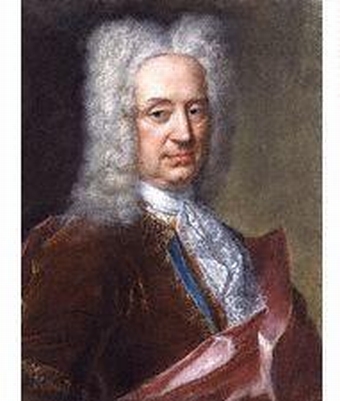

Charles Whitworth (1675-1725) served three British sovereigns: William III, Anne and George I. He fulfilled diplomatic missions of first importance, e.g. in Berlin during the close of the Great Northern War (1719-1722), or as minister plenipotentiary at the Congress of Cambrai (1722-1725). Whitworth was involved in both diplomatic issues of the Northern and Southern European theatres, including the rise of Russia, the intricacies of religious politics in the Holy Roman Empire and the complex legal aftermath of the succession of Charles II of Spain (1661-1700). He was a key figure in the complex British foreign policy of the Hanoverian succession.

Born in 1675, Charles Whitworth was educated at Westminster and Trinity College Cambridge (of which he became a fellow in 1700) and was buried in the south aisle of Westminster Abbey on 6 November 1725. He started as secretary to George Stepney (1663-1707), William III’s envoy in Berlin, then acted as aide to Cardinal Lamberg, commissioner of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, at the Regensburg Diet at the beginning of the War of the Spanish Succession, and then replaced Stepney in Vienna (Santifaller 1950).

Whitworth’s stay in St Petersburg, in extremely difficult days, from 1704 to 1713, produced a remarkable Account of Russia in the Year 1710 (Whitworth 1758; Hartley 2002). This country had been “so little frequented by Foreigners, and their Share in the Affairs of Europe so inconsiderable”. Whitworth became involved in the famous case of the Russian ambassador Mathweof, held in London for private debts in 1708 (Martens 1827). Mathweof had been arrested after his final audience with Queen Anne, at the end of his diplomatic mission, but quickly released on bail. The Privy Council ordered the arrest of several British subjects. The jury in the Queen’s Bench declared them guilty, but failed to impose a retroactive penalty. Whitworth obtained the highest diplomatic rank, that of ambassador extraordinary, to apologize with the Czar.

Whitworth described Russia with distant irony: “The peasants, who are perfect Slaves, subject to the arbitrary Power of their Lords […] can call nothing their own, which makes them very lazy”. (Whitworth 1758: 185). This primitive mass of peasants seemed “admirably fit for the Fatigues of War”, ready to “go as unconcerned to Death or Torments, and have as much passive Valour, as any Nation in the World” (Whitworth 1758 186). The Czar ruled “absolute to the last degree, not bound up by any Law or Custom, but depending on the Breath of the Prince” (Whitworth 1758: 189). The Orthodox Church was seen as “corrupted by Ignorance and Superstition” (Whitworth 1758 186). During the last months of Queen Anne’s reign, Whitworth was sent to Augsburg, to observe the conference in Baden between France and the Emperor. Berlin and again The Hague followed. He was also in post at Berlin, Vienna and the Palatinate amidst the complications of the Great Northern War.

Western and Southern European politics after the Peace of Utrecht (1713) were extremely complicated. The Cambrai Conference (1722-1725) served to complete the Treaty of the Quadruple Alliance, mainly its fifth article, specifying the right of succession to the duchies of Parma and Piacenza and the Grand-Duchy of Tuscany, destined to be inherited by the offspring of Philip V of Spain and his second wife Elisabeth Farnese. This would take another seven years. Whitworth had been made an Irish peer in January 1721 (“Baron Whitworth of Galway”) and entered the House of Commons as an MP for Newport (Isle of Wight) in 1722. He joined Polwarth (Alexander Campbell Hume, the later second Earl of Marchmont (1675-1740)) at Cambrai in the Autumn of 1722. The Italian duchies implied the application of feudal law. Would Philip V’s son become a “loyal” vassal of the Emperor, or even a “subject” or a “liege vassal”? A final peace treaty between Charles VI and Philip V was still due. Which titles could Philip V and Charles VI assume, irrespective of the territory they effectively controlled? Who inherited the grand mastery of the Golden Fleece?.

The extent to which imperial and feudal law had been altered by the Quadruple Alliance provided ample opportunities for delays and obstruction. Memoranda in Latin from the Imperial Court Chancery were rigorously scrutinized by university educated British diplomats, juggling with legal terms, draft treaties and synoptic tables. Their judgment of Spanish arguments was devastating, even in cases where the Spanish view ought to have prevailed. The discussions on Sienna at the decease of Grand Duke Cosimo III of Tuscany showed Whitworth and Polwarth’s irritations with Spain’s excessive claim on sovereignty. Yet, the Austrian answers were so weak, that “the Reasons of the Imperialists may be very justly disputed, thô the thing in itself could not, had it been rightly understood.”

By late August 1724, Whitworth and Polwarth outstepped the boundaries of their role, challenging George I’s foreign policy. Franco-British rivalry seemed permanent, the embellishment in mutual relations temporary. Whitworth looked at the French court with irritation. Louis XV was spoiled by his entourage: “the only attention of the D[uke] of O[rléans] and the others about him is to please him in every thing, and teach him nothing.”

The British plenipotentiaries felt they had conceded the leadership to the French delegation. After Cardinal Dubois’s and the Regent’s decease, the bishop of Fréjus had become the new strong man at Court in Versailles, “a trifling genius, and a little mysteriousness in his temper, with a love of chicane, which makes it difficult to act with him in confidence”. Polwarth and Whitworth feared a turnaround in French policy, especially against the background of incidents with Protestants in the Empire (Whaley 2011: 156). The French, they feared, were “Jacobites in their hearts”. A “Catholic League” could well emerge under Fleury, who seemed to keep a private correspondence with the Austrian plenipotentiary Penterriedter.

The only solution, Whitworth and Polwarth argued, was for George I to take up the role of “umpire in a manner of the affairs of Europe”, and mediate –alone- between a Catholic Franco-Spanish-Italian bloc, on the one hand, and a Prussian-Dutch-Imperial camp, on the other. George should have used his experience at the age of 64 to dominate the young monarchs of France (14) and Spain (17). An independent British course would oblige the other sovereigns to go for “Pace con l’Ingleterra e Guerra con tutta la terra”.

Newcastle severely reprimanded them. Foreign policy was not a matter of affect, but of interest: “unless Your Ex[cellen]cys are of opinion that England should never have to do with any Countrey, that has in any particular different views from us, or whose Interests are not inseparable from our own.”

References

Dhondt, F. (2015)

Balance of Power and Norm Hierarchy. Franco-British Diplomacy after the Peace of Utrecht. Leiden/Boston: Martinus Nijhoff/Brill.

de Martens, F. (1827)

Causes célèbres du droit des gens. Leipzig : Brockhaus.

Whaley, J. (2011)

Germany and the Holy Roman Empire. Volume II: The Peace of Westphalia to the Dissolution of the Reich, 1648-1806. Oxford: OUP.

Whitworth, C. (1758)

An Account of Russia as it was in the Year 1710. Strawberry-Hill.

Suggested reading

Thompson, A. (2006),

Britain, Hanover and the Protestant Interest, 1688-1756. Woodbridge, Boydell Press.

Aldridge, D.D. (2004). “Whitworth, Charles, Baron Whitworth (bap. 1675, d. 1725)”,

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29336, accessed 22 April 2016].

Dureng, J. (1911).

Le duc de Bourbon et l’Angleterre (1723-1726). Toulouse : « du Rapide ».

Hartley, J.M. (2002).

Charles Whitworth: Diplomat in the Age of Peter the Great. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Santifaller, L. Gross, L. &. Haussmann F. (ed.) (1950),

Repertorium der diplomatischen Vertreter aller Länder seit dem Westfälischen Frieden, Band. 2: 1716-1763. Zurich: Fretz & Wasmuth.